Hoof health management in cattle is essential in bettering the welfare of the animal, but also in reducing disease prevalence and economic losses.

Inadequate hoof health can lead to decreased feed intake, low body mass index, low productivity gains, decreased lifespan and impaired reproductive health.

To prevent these outcomes, it’s important to isolate the cause of hoof health deterioration and prevent this from worsening in the herd.

Factors such as environmental, nutrition, or disease can all be contributing influences.

Important questions to ask yourself:

- How long can you predict the cattle to be living in this circumstance? Is this manageable?

- If the environment is problematic, is there the ability to move cattle to a cleaner environment?

- What nutrients are in the feed?

- Are there any signs of disease? (Lameness in the herd? Infection?)

Environmental

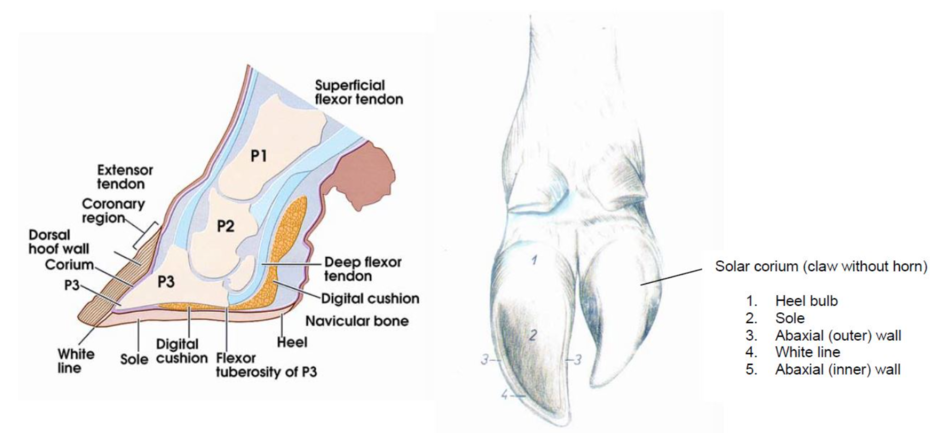

The current La-Nina climate has proven to be extreme and relentless with the enormous quantities of rainfall sweeping over Queensland and Northern New South Wales. These conditions make it difficult to keep cattle clean and dry, thus exacerbating poor hoof health. Constructed of cornified epidermal tissue called ‘horn’, the hoof capsule (see Figure 1) plays a vital role in both biological and mechanical functions (Budras, K. D et al. 1998).

Anatomically, the horn protects underlying tissues by acting as a cushion, and mechanically it transmits the animal’s weight from the skeleton to the ground (Jeanne, B. et al. 2000). Rainwater and cow slurry (urine and faecal droppings) contribute to softening of this protective barrier, and in turn can cause degradation of the hoof (Babintseva, T. et al 2020). When cattle have prolonged exposure to these conditions hoof integrity declines, posing a risk to the animal of contracting anaerobic bacterium (Currin, Whittier and Currin, 2005).

For that reason, it is important to minimise your herd’s exposure to these conditions, whether this be removing cattle from wet conditions (shifting herd to high and dry land) or supplying stabled cattle with fresh bedding such as sand or sawdust. This bedding will help to absorb moisture and reduce pressure load on the hoof. Cattle kept in smaller paddocks may also be split between multiple paddocks to reduce stocking density and reduce impact upon soil quality.

Nutrition

Hoof structure and quality is dependent on the keratinization process, which is influenced by nutrient supply from amino acids, lipids, vitamins, and minerals. Minerals in the form of zinc, sulphur, copper and calcium aid in the development of blood vessels and alveoli, which in turn assist in the permeability of the cell membranes and functional activity of immune cells (Babintseva, T. et al 2020). Without the appropriate function of immune cells, histamines are released within the animal’s body after grain consumption that form labile bonds with the proteins of the hoof horn.

These bonds contribute to rheumatic inflammation, due to the onset of inflammatory processes that often lead to tissue necrosis (Samolovov and Lopatin, 2011). Structural abnormalities are a common sign of tissue necrosis, caused by poor hoof conformation, which increases the importance of completion of the keratinization phase.

A finding has proven there is no great significance between different mineral sources, in particular zinc and copper, in the development of hoof diseases. Whether minerals were supplied in a mixture of organic and inorganic or solely as hydroxyl trace minerals, the animal’s mineral uptake was not interrupted (Hilscher, H. F et al. 2019). Ultimately, several nutrients are vital in the formation and growth of the hoof.

Disease

A result of animal husbandry intensification has seen associations of diseases in cattle attributed in the distal extremities, mostly the hooves. It is claimed that up to 60% of a culling population are recognized with distal diseases caused from unmanaged microflora (Samolovov and Lopatin, 2011).

Foot Rot is a highly infectious bacterial disease transmissible from manure and infected hooves. The bacteria F.necroforum invade and cause disease when the animal’s skin is broken interdigitally (between the toes, as seen in Figure 1). Infected cattle will then further contaminate the environment, as the bacterium can survive in the environment for as long as ten months (Edmundson, A, J. 1996).

Other common diseases include Laminitis and Foot Abscesses, which have sudden onset lameness ramifications. Laminitis presents symptoms of increased digital pulse (between the toes) and increased hoof temperature, while foot abscesses present swelling of the hoof and discolouration of the sole with associated tenderness (‘Livecorp’, 2022). All diseases should be managed appropriately and you may require veterinary advice in finding an effective treatment.

Management

Setting up a copper sulphate footbath helps to disinfect and harden hooves. This should be installed in an interactive zone such as an entryway to a feedlot to ensure all cattle are accounted for. DO NOT allow cattle to drink this solution.

Consider spreading sawdust, crushed limestone or sand on highly trafficked laneways to assist in relieving pressure on hooves and raising cattle off harsh flooring (e.g. wet concrete/stones/mud). This also reduces the chance of stones from being carried in from the laneway and ‘shredding’ the soles of hooves.

Make sure feedlot pens are regularly cleaned and scraped – it is important to make sure there is no manure, mud, or gravel (causes stone bruises) as these create the perfect environment for rough ground to weaken hooves and for bacteria to thrive.

Where possible, separate lame cows at the first sign of lameness, and keep lame animals close to feed and water to reduce their walking distances.

In muddy conditions, reduce the herd’s walking distance if possible. Strip grazing paddocks will work, however, more rotation is needed to discourage soiled environments.

Consider building feedlots on a slope to encourage drainage.

To sum up, there are many factors that influence hoof quality, so it is important to maintain hoof health regularly. It is important to have measures in place when hoof health is compromised to reduce the economic loss that stems.

For further advice on feeding cattle with hoof health issues, we encourage you to contact your nominated Riverina representative or branch.

Natalie is a certified animal nutritionist for Riverina Stockfeeds, and particularly enjoys working with pigs. She has a Bachelor’s degree in Veterinary Nursing and is new to the Riverina team.

References

Babintseva, T, Mikheeva, E, Shishkin, E, Yudin, V, Klimova, E & Shklyaev, K. (2020) ‘Studying the Factors Affecting the State of Cattle Hoof Horn’, Advances in Animal and Veterinary Sciences, 8(3), pp.11-17.

Budras, K. D, Geyer, H, Maierl, J & Mülling, C (1998) ‘Anatomy and structure of hoof horn’, Symposium on Lameness in Ruminants, pp. 176-188.

Currin, J.F, Whittier, D.W & Currin, N (2005) ‘Foot Rot in Beef Cattle’, Virginia Cooperative Extension, pp.1-3.

Edmonson, A.J (1996) ‘Interdigital Necrobacillosis (Footrot) of Cattle’. Large Animal Internal Medicine (2).

Gooch, C.A. (2003) Foot Anatomy. Available at: www.vet.cornell.edu/animal-health-diagnostic-center/programs/nyschap/modules-documents/foot-health (Accessed: 21 July 2022)

Hilscher, H.F, Laudert, S.B, Heldt, J.S, Cooper, R. J, Dicke, B.D, Jordon, D. J, Scott, T. L, & Erickson, G. E. (2019) ‘Effect of copper and zinc source finishing performance and incidence of foot rot in feedlot steers’, Applied Animal Science, 35, pp.94-100.

Jeanne, B, Perkins, K, Chaiyotwittayakun, A & Erskine, R. J (2000) ‘How Do Nutrients Affect the Immune System?’, Tri-State Dairy Nutrition Conference, pp.1-193.

‘Livecorp’ (2022), Foot Abscess. Available at: www.veterinaryhandbook.com.au/Diseases.aspx (Accessed 27 July 2022)

Samolovov A. A, Lopatin S.V, (2011). Laminit krupnogo rogatogo skota. Cattle laminitis’, Siberian Herald of Agricultural Science, pp. 71-77.

Beef

Beef

Dairy

Dairy

Sheep

Sheep

Horse

Horse

Pig

Pig

Goat

Goat

Poultry

Poultry

Bird

Bird

Dog

Dog

Special

Special

Feed Materials

Feed Materials